At the end of May 2007, I found myself in Alice Springs for a couple of days as part of a tour of Aboriginal communities and art centres sponsored by Austrade. We had an afternoon free and so I made arrangements to catch up with Daphne Williams, the longtime heart, soul, and backbone of Papunya Tula Artists. There’s always plenty of news to share, but I wasn’t expecting or prepared for one story Daphne had for me.

At the end of May 2007, I found myself in Alice Springs for a couple of days as part of a tour of Aboriginal communities and art centres sponsored by Austrade. We had an afternoon free and so I made arrangements to catch up with Daphne Williams, the longtime heart, soul, and backbone of Papunya Tula Artists. There’s always plenty of news to share, but I wasn’t expecting or prepared for one story Daphne had for me.

She asked if I’d heard the news about George Rrurrambu. Bone cancer; he doesn’t have long. “I was always fond of him,” Daphne said, “even if he was a real hellraiser when he was young.” I was shocked by the news, and almost equally surprised at the thought of Daphne and George being friends, for on the surface of things, you could hardly imagine two more dissimilar personalities. But now, looking back with a few years’ perspective, I find it easy to believe that two people with such large, warm hearts would be fond of one another.

These thoughts came back to me last night while I was watching Big Name, No Blanket (Night Sky Films, 2013, directed by Steven McGregor), the new documentary about the late lead singer for the Warumpi Band, .

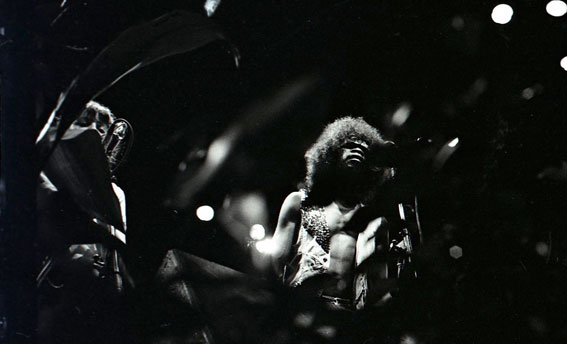

The film is in many ways a standard biopic. There are lots of interviews with people who knew the singer well throughout his life, including his wife Suzina, his children, bandmates Neil Murray and Sammy Butcher, other musicians like Lou Bennett and Shane Howard, and desert filmmakers Rachel Perkins and Warwick Thornton. There are clips from a couple of the Warumpi Band’s music videos (the ground-breaking first-song-in-language “Jailanguru Pakarnu” and the perennially popular “My Island Home“) and from the film of their 1986 Black Fella While Fella tour with Midnight Oil. And there are many other, all too brief scenes from concert dates around Australia, from early days in Papunya through their hell-raising farewell performance at Stompen Ground in Broome in 2000.

The film is in many ways a standard biopic. There are lots of interviews with people who knew the singer well throughout his life, including his wife Suzina, his children, bandmates Neil Murray and Sammy Butcher, other musicians like Lou Bennett and Shane Howard, and desert filmmakers Rachel Perkins and Warwick Thornton. There are clips from a couple of the Warumpi Band’s music videos (the ground-breaking first-song-in-language “Jailanguru Pakarnu” and the perennially popular “My Island Home“) and from the film of their 1986 Black Fella While Fella tour with Midnight Oil. And there are many other, all too brief scenes from concert dates around Australia, from early days in Papunya through their hell-raising farewell performance at Stompen Ground in Broome in 2000.

In this respect the film enlarges upon the earlier ABC documentary about the band, The End of the Corrugated Road. (The new film clocks in at just under an hour, twice the running time of the earlier feature.) Any film project about the Warumpis is going to find its focus in the outsized personality of the band’s frontman, but much of the story here is told by those who knew him, even more so than through the interview clips with—as Neil Murray refers to him—G.R. himself. As a result, Big Name No Blanket isn’t simply a biopic of one man. Rather, G.R. comes to embody—much as he did back in the day—what the entire band and its story meant and continues to mean to their legions of fans, blackfella and whitefella alike.

The band is a legend; there’s no disputing that. The first rock ‘n’ roll single to be sung in an Indigenous language; the band whose tutelage brought Midnight Oil to the creative peak of their own career with Diesel and Dust, the Oils’ album that grew out of the joint tour; the performance of “My Island Home” by Christine Anu at the closing ceremonies of the Sydney Olympics in 2000; the song “Blackfella/Whitefella” itself the anthem of reconciliation: all these are indelible markers in the renaissance of Indigenous culture in Australia in the final decades of the twentieth century. One of the great strengths of Big Name No Blanket is the way in which it revivifies the legend and sends back into your heart the jolt of excitement all those events generated .

Because I have to admit, over the years, I’ve become a bit jaded, begun to take the Warumpis, and even G.R. himself, a bit for granted. I groan whenever a film or a television show, needing to dramatize a feelgood moment, decides to splice in a troopie full of characters singing along with “Blackfella/Whitefella” on the radio. Or when “My Island Home” gets pressed into similar service as a land rights lullaby. There are times when it’s all a bit cringe-inducing, like the millionth time an elevator door closes and you find yourself listening to the strains of the Beatles’ “Yesterday” or worse, “Michelle”.

Big Name No Blanket manages to scrub away a lot of that accumulated overdose and reveal just how buzzworthy the Warumpis were thirty years ago, and better, makes you realize how thrilling they still are. The concert footage certainly helps: the blistering version of “Kintorelakutu” (my personal, all-time, best-of, favorite Warumpi song) filmed on an early tour of the Kimberley, or the crunching chords of “From the Bush” and “Warumpinya” that make you realize how much the band owes to AC/DC as well as to Chuck Berry. But some of the most powerful moments in the film are in fact, much to my surprise, centered on the stories of “My Island Home.”

I bought the Warumpis’ first two albums many years ago in a record store tucked into a major shopping mall in the Brisbane CBD. At the time I didn’t know a lot about the Band itself apart from the fact that they’d been on a bush tour with Midnight Oil. I’d found the first album, Big Name, No Blankets, in a bin and taken it up to the counter, where the clerk asked, “Don’t you want their other album? The one with “My Island Home”? I just love that song.” (In fact, I did want Go Bush! as well, but couldn’t find it; their only remaining copy was behind the counter for playing in the store, and they were kind enough to sell it to me.) For lots of people, it seemed, the Warumpi Band began and ended with “My Island Home.”

I bought the Warumpis’ first two albums many years ago in a record store tucked into a major shopping mall in the Brisbane CBD. At the time I didn’t know a lot about the Band itself apart from the fact that they’d been on a bush tour with Midnight Oil. I’d found the first album, Big Name, No Blankets, in a bin and taken it up to the counter, where the clerk asked, “Don’t you want their other album? The one with “My Island Home”? I just love that song.” (In fact, I did want Go Bush! as well, but couldn’t find it; their only remaining copy was behind the counter for playing in the store, and they were kind enough to sell it to me.) For lots of people, it seemed, the Warumpi Band began and ended with “My Island Home.”

The song has a vexed history, as many legends do. It was a huge commercial hit for Christine Anu, not for the Band, ten years after they broke it on the radio. And it was Christine Anu who got to perform at the Olympics. Neil Murray movingly relates how hurt G.R. was by that incident, how G.R. believed he should have been the one making that eloquent statement of land rights at that crucial moment when Australia had the international stage.

Sadly, there’s no mention in the film of the other performance at those closing ceremonies that directly addressed the issues of land rights and reconciliation. It was given to Midnight Oil to take that message to the world with their performance of “Beds Are Burning” in their black trackies emblazoned with the word SORRY. Although their performance and its strident rebuke of John Howard was an absolutely thrilling moment, there is a cruel irony in the fact that the band that embodied reconciliation, that galvanized audiences, that demanded that everyone “stand up, stand up and be counted” was nowhere to be seen or heard that night.

Murray also talks about the other long-standing, problematic legend relating to “My Island Home,” the question of its authorship. Murray states that he wrote the song for G.R., and indeed it tells the story of the saltwater man marooned in the desert, far from his country (much as Murray himself was far from his Victorian roots). Over time, G.R. came to regard the song as his own. As Murray says, in G.R.’s mind, the song belonged to the singer and not to the author. It’s clear that the confusion, the accusations that Murray somehow co-opted G.R.’s ownership, have hurt Murray over the years; it’s equally clear that he remains steadfast in his own beliefs about copyright and intellectual property while recognizing that G.R. saw things very differently. This vignette does a lot to demonstrate how the respective cultures of blackfellas and whitefellas operated in the band, how the visions worked together and sometimes at odds with one another.

The films tackles a lot of the tensions that defined the Warumpis’ history: Neil’s desire to build a big, professional career, the Butchers’ will and obligations to stay close to Papunya that frustrated Murray, and above all, G.R.’s hell raising antics that cost the band business and clearly raised Murray’s blood pressure. It doesn’t simplify the stresses. It takes a chestnut of “reconciliation” and burnishes it to reveal the complications, the give and take, and the pain that surrounds the issues. In doing so, it somehow re-animates not just “My Island Home” and “Blackfella/Whitefella,” but the whole legend, the thrills and the stumbles of what the Warumpis represented in those exciting days when the band was creating a new consciousness.

And finally, there is G.R.’s exquisite ultimate rendition of “My Island Home” with the Black Arm Band, only months before his death. If you haven’t seen the performance, I’m not going to spoil it for you by describing it in detail. But it is a moment that shows how much the song ultimately came to belong to the singer, not the least for it’s being sung in yolngu matha. It’s much like the version that can be heard on G.R.’s single solo recording, Nerbu (Message), from 2004, and it’s the version that I saw a different incarnation of the Black Arm Band perform earlier this year here in America.

There’s a scene in Big Name No Blanket in which the Warumpis are shown performing “Blackfella/Whitefella” at Stompen Ground, the concluding bit where the music drops out and G.R. exhorts the audience to sing, unaccompanied, “stand up, stand up and be counted.” Then he exhorts them to jump while they sing. The entire hall is buzzed, arms stretched high above their heads in imitation of G.R.’s energy, bouncing up and down, singing along with all their might. It’s one of those moments of utter abandon and exhilaration. G.R.’s final performance on “My Island Home” with the Black Arm Band back in 2006 was another, and it reminded me how here in America, where probably fewer than a dozen people in the audience that night last February knew the Warumpis, Emma Donovan and the Black Arm Band managed to get the entire auditorium to join them in singing out over and over again, “my island home is a-waiting for me.”

Such is the power of the Warumpi Band; such is the charisma of George Rrurrambu Burarrwanga. If you’re new to the Band’s magic, Big Name No Blanket will act as a superb introduction to the legend, and there’s just enough of the music there to get you hooked. If like me, you’ve basked in the glow of the Warumpis for a long, long time, the film will regenerate the rush that came with discovering them for the first time. In either case, you’ll come away with a nuanced appreciation of their history, their struggles, their achievements. G.R. is often compared to Mick Jagger or to James Brown for his sheer energy and presence onstage. But for me, the Warumpi Band is better perceived in light of Elvis Presley or the Beatles. Not because there’s necessarily a strong musical kinship, but because after Presely and the Beatles, nothing was ever the same again. And that is true of the Warumpi Band as well. Big Name No Blanket is an exquisite reminder of that fact, and a renewal of my faith in the meaning of rock ‘n’ roll.

Here’s the trailer for Big Name No Blanket; there’s another video on YouTube in which director Steven McGregor and co-producers Lisa Watts and Rachel Clements discuss the background and making of the film. (Photos here are from the BNNB FB pages.)