Guest post by Glenn Manser

[Note: Glenn first reached out to me in January 2006, about three months after I started this blog. Since then he has been a faithful correspondent, exchanging perspectives on trends in Aboriginal art, the performance of the market, and the characters encountered on our ways. He’s sent me probably hundreds of newspaper stories (of the internet kind) over the years. Oddly, we’ve never really met: as I said a couple of weeks ago on Facebook, we’ve howdied but we haven’t shook. The closest we’ve come to a face-to-face meeting was a greeting shouted across the forecourt of MAGNT at the NATSIAAs in 2008 (I think that was the year) as I was getting in a car to catch a lift to the Botanical Gardens and he was lining up to enter the exhibition. So it gives me great pleasure to move our collaboration up another notch with this report from Desert Mob and Alice Springs. You can read more about Glenn’s passions in this recent QAGOMA blog post.]

As I left the plane at Alice Springs Airport over a fortnight ago for the Desert Mob weekend, I was reminded of Duncan’s words in Macbeth:

…the air

Nimbly and sweetly recommends itself

Unto our gentle senses

Fortunately my experience of Desert Mob was vastly more pleasing than Duncan’s visit to Glamis.

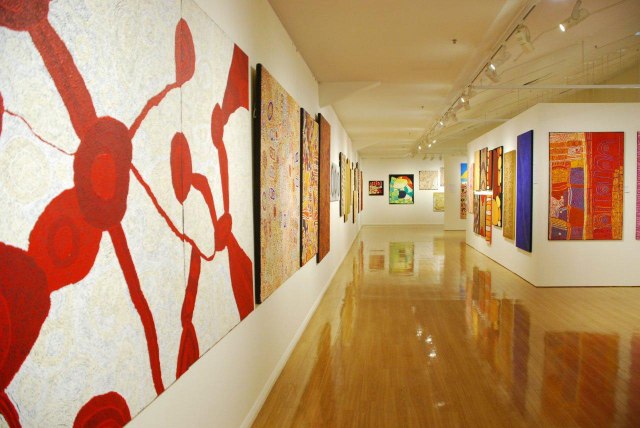

When Desert Mob is discussed, it should be in its widest context. Not only is it the actual exhibition at the Araluen Centre, the symposium and Marketplace but also the accompanying exhibitions at Papunya Tula Artists, Talapi Gallery and Raft Artspace. Collectively they provide a density of experience of Western Desert art that is not replicated anywhere.

After a four year hiatus, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect from this Desert Mob weekend. As usual, Araluen Cultural Precinct Director Tim Rollason had everything running ship shape and Curator Stephen Williamson again did an impressive job with the hang. (All entries in the exhibition can be found at Desert Mob 2014 | Desart.)

The key to this Thursday afternoon is to purchase the catalogue, queue, wait for the opening pleasantries to pass and then scamper into the galleries, do a quick reconnoitre and pluck the appropriate ticket from the item or items you wish to purchase. There is no time to think, consider, evaluate. With over 31 art centres spread throughout three galleries, it is important to be tactical as to which gallery is chosen to sprint to first.

Gallery 1 seemed to offer an interesting combination of art centres. It was the ceramics rather than the paintings that immediately caught the eye. The juxtaposition of the Ernabella and Hermannsburg displays highlighted the divergent styles that have emerged at both centres. Alison Carroll’s beautifully marked stoneware, Ngayuku Walka, reminiscent of her prize winning piece in the Shepparton 2014 Ceramic Art Award (Alison Carroll – Shepparton Art Museum) stood imperiously in all its jade coloured glory. Amusingly nearby, and acquired by the Araluen, was Rona Rubuntja’s Artist Car, an earthenware, paper clay and underglazes rendition of the great Albert Namatjira’s ute, in a well-worn, outback green.

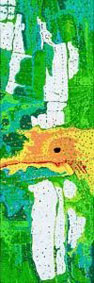

Again it was the Ernabella paintings that next took the eye with a beautifully executed hazy golden piece by Yurpiya Lionel, a fine Rupert Jack and an elongated yet warmly textured Wanampi by Gordon Ingkatji, also acquired by the Araluen. Other pieces of note included a husband and wife collaboration by Tjungu Palya artists, Keith and Tjampawa Stevens and a superb representation of Punyunya by Spinifex artist, Fred Grant.

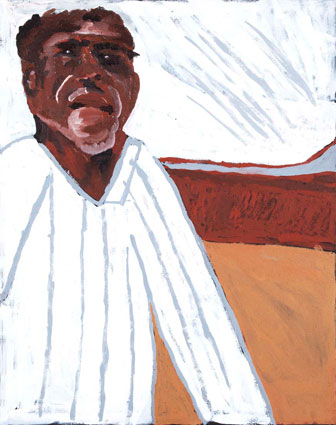

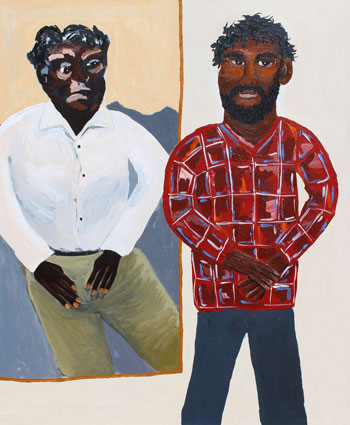

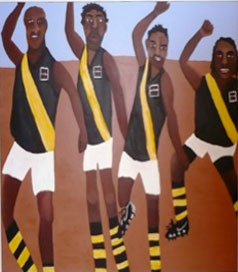

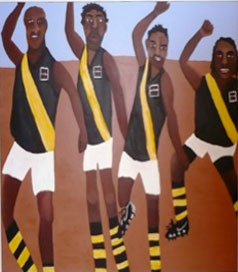

Equally fascinating was up-and-coming Iwantja artist Vincent Namatjira’s insightful execution of The Idulkana Tigers, spotlighting the transformative role Australian Rules Football (AFL) plays in the lives of young, outback Indigenous men.

Equally fascinating was up-and-coming Iwantja artist Vincent Namatjira’s insightful execution of The Idulkana Tigers, spotlighting the transformative role Australian Rules Football (AFL) plays in the lives of young, outback Indigenous men.

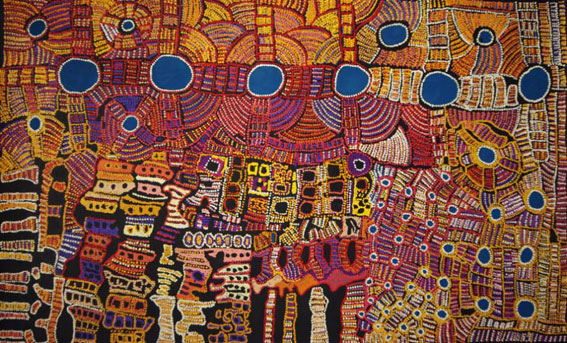

The Papunya Tula Artists selection was again a collection of masterful smaller pieces that segued beautifully to its own gallery hang. The Morris Gibson Tjapaltjarri, Ray James Tjangala and Mantua Nangala, in particular, stood out. Across the aisle new Papunya Tjupi Arts’ coordinator Helen Puckey had also assembled a collection of praiseworthy pieces including a subtly complex piece in muted yellows by Isobel Gorey Nampitjinpa and a Doris Bush Nungarrayi kaleidoscopic rendition of women searching for bush food.

The Tjanpi Desert Weavers displays were a big hit with extravagant collections of emu, wedge-tailed eagles and an assortment of other birds executed in raffia, feathers, acrylic yarn and wire dominating the floor space. A profusion of red dots was quick testimony to their popularity.

Unfortunately, and it pains me to say it, but the Warlayirti Artists’ exhibition was just plain disappointing. While there were some old favourites, including Bai Bai Napangardi and Helicopter Tjungurrayi, it was the sameness of the selection, even after a four year absence, that really surprised. Hopefully with new coordinators in place, this art centre can bring on some of the younger artists and regain some of Balgo’s former glory.

Gallery 3 and the smaller Sitzler Gallery proved to be less even in their offerings but there were some jewels to be found.

Tjala Arts again dominated with a profusion of large canvasses including a memorable senior women’s collaboration titled Nganampa Ngura. It was with much sadness that during the exhibition news reached Alice Springs that Kunmanara Williamson, one of the collaborating artists, had passed away.

Tjala Arts again dominated with a profusion of large canvasses including a memorable senior women’s collaboration titled Nganampa Ngura. It was with much sadness that during the exhibition news reached Alice Springs that Kunmanara Williamson, one of the collaborating artists, had passed away.

It was a playfully collaborative work of acrylic on linen together with spinifex fibre and raffia-like reptiles by May Pan and Iluwanti Ken that generated interest and good humoured banter.

Kayili Artists made a memorable return with a series of 80 x 60cm boards with Mrs Ward and Nola Campbell, in particular, delivering very strong works in shimmering colours. Not to be outdone Tjarlirli Art provided two striking works; an abstracted piece in muted browns and infused blues by Bob Gibson and a delicious mixture of swirling reds, oranges and greens in Nyarapayi Giles’s Warmurrungu.

A diverse collection by Martumili Artists provided two impressive pieces by Jakayu Biljabu and the evergreen Nora Wompi.

It was in the Sitzler Gallery that opening night, by then, drew to a conclusion. Watercolours by Kevin Namatjira and Reinhold Inkamala stood out with the latter’s brooding atmospherics characteristic of his emerging style.

For an alternative perspective on opening day and the symposium that followed, Kieran Finnane always provides insightful commentary – Desert Mob: This is who we are – Alice Springs News.

As previously mentioned the weekend was enriched with three quality exhibitions at Papunya Tula Artists, Kate Podger’s Talapi Gallery and Dallas Gold’s Raft Artspace, all nicely segued to sections of the Desert Mob exhibition.

Papunya Tula Artists has been Alice Springs’ epicentre for Central Australian Indigenous art, recently celebrating 40 years of service to its shareholders, principally the Pintupi people. To coincide with Desert Mob, Manager Paul Sweeney and team rehung the gallery and what a fine, carefully nuanced exhibition it was.

The stylistic changes in Morris Gibson’s latest works were evident and a sequential development from his rectangular, richly hued piece in Desert Mob obvious.

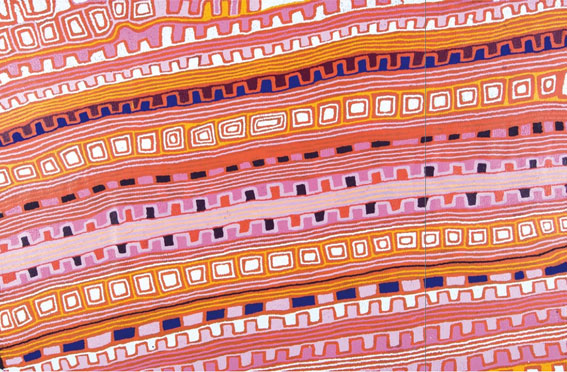

Nearby was a mini exhibition of contemporary pieces, large and small, by Yinarupa Nangala finely juxtaposed to emphasise her command of space and minimal use of colour to evoke country.

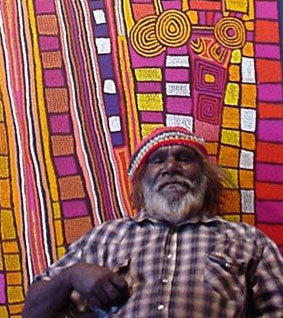

It was a real treat to meet Patrick Tjungurray again as he sat quietly in the gallery. Six or so years had passed since he had graced the gallery in a triumph of the Tjungurrayis, surrounded by a gaggle of admiring relatives and collectors. Now the ravages of time and ill health were evident. A small but significant selection of his work, however, referenced his enduring strength as an artist and a chronicler of his country and its stories. Thoughtfully juxtaposed next to the colour and vibrancy of Tjungurrayi’s work were several by Ray James Tjangala. The four or so works by Tjangala provided a compositional point of comparison between these two great exponents of Western Desert art. As Sweeney commented, “The work by Ray is undoubtedly typical of him. It’s tight with a quirky twist. I believe a good Ray has a bit of something left field in it which this one does.”

Of course there was much more to admire in the gallery including mini solos by Nunyuma Napangati, Josephine Nangala and Kawayi Nampitjinpa and a veritable feast of attractive smaller 61 x 31cm pieces that adorned the gallery’s main wall.

Entering Kate Podger’s Talapi Gallery, just up the mall, presented an immediate kaleidoscopic contrast to Papunya Tula with a hang of largely Tjungu Palya sourced work on the walls. A profusion of bright reds, greens, blues and everything in between greeted you in her “Desert Colour” exhibition. A gorgeously rich Iyawi Wikilyiri, a small but equally sumptuous Maringka Baker, a Helen Curtis composition of color contrasts, Keturah Zimran’s bold colour fields and a richly rendered Betty Kuntiwa Pumani from Mimili Maku Arts, among many others, gazed at you from the walls.

Kate, former curator at the Araluen Cultural Centre and manager of Ros Premont’s Gallery Gondwana, always brings a depth of knowledge and commentary to any discussion about the qualities of paintings and artists. The set of paintings chosen for the exhibition beautifully complimented the larger collaborative Tjungu Palya and Mimili Maku pieces in Desert Mob.

The third exhibition to round out the Desert Mob weekend was at Dallas Gold’s Raft Artspace and what an experience it was. In the split gallery there was Carlene West’s first solo and also an Ernabella ceramics exhibition.

In the accompanying glossy catalogue, Claire Eltringham said of West’s paintings;

The simplistic compositions boast vast gaping spaces in high contrast colours, the curves are seductive and freeform, the artist’s marks resolute and undaunted…To the naked eye, this is an expansive salt lake, without vegetation, pale but mesmerising with only the tracks in the sand capturing any movement…This is Spinifex country-raw, unforgiving and expansive… as a stand -alone body of work, these paintings are avant-garde and mesmeric.

Given the number of red dots circling the gallery, collectors agreed with Gold’s uncanny ability to unearth new talent, even if West has been painting since the Spinifex Project actually began. He was his self-effacing self when describing the virtues of both exhibitions to the assembled audience.

Indeed, the sensation was as if one was absorbed into those vast expanses that provide the inspiration for West’s paintings.

Just as amazing were the ceramics that made up the Ernabella Arts Tjulpirpa wiya – clay! Not mud-clay exhibition in the smaller gallery. Composed entirely of works by male artists, this stunning exhibition presented works of quality and imagination. Following on from the highly successful key note exhibition Tjungu Warkarintja, Fifteen Years | sabbia gallery, the decision to concentrate on the male artists was inspired and well received.

The talented Ngunytjima Carroll throws most of the pots at Ernabella but rarely marks them. His two pieces in this exhibition reflected not only his ability to shape but also to mark strongly and creatively. Equally, Derek Jungarrayi Thompson, Pepai Carroll and Andy Paul Tjutjuna bring their own gifts to pot marking. Thompson has a beautifully refined, even delicate aesthetic to his interpretation of the Wanampi Tjukurpa, Pepai Carroll marks his Walungurru strongly yet conservatively and Andy Paul Tjutjuna, both in his Desert Mob and Raft pieces, boldly works in shades of black, occasionally infusing blues into his Kalaya Tjukurpa.

Is Desert Mob still the artistic counterpart to Telstra, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Award, it once was? Well, if the experiences above are any indication, it is not only alive but definitely doing very well indeed. When the Indigenous art community puts its mind to it, there is nothing better than Desert Mob in Alice Springs.

–Glenn Manser

Having thoroughly enjoyed Vivien Johnson’s previous book,

Having thoroughly enjoyed Vivien Johnson’s previous book,

The story of Papunya painting in the 80s and 90s as Johnson tells it is for me the emotional center of Streets of Papunya, although I must say up front that that is a most personal judgment, reflective of my own history far more than Johnson’s. The first Papunya painting that I owned was a brilliant Water Dreaming by Long Jack Phillipus. The most startling early Papunya board I’ve ever fallen in love with is a Crow and Yam Dreaming by Limpi (at right), an artist I had never heard of until I saw the work reproduced in an auction catalog. For some reason I could never recapture, I was fascinated by the work of Two Bob Tjungurrayi; now having read Johnson’s book I understand that the brilliance of Turkey Tolson’s Straightening Spears paintings owes a great deal to stylistic innovations that Limpi and Two Bob undertook in the late 80s, before Turkey and his fellow innovator, Mick Namarari, themselves left the streets of Papunya behind. Reading about the heyday of Warumpi Arts, then located on Gregory Terrace around the corner from the old Papunya Tula shop, made me remember how thrilling it was in those days to be discovering the genius of the art of the central desert.

The story of Papunya painting in the 80s and 90s as Johnson tells it is for me the emotional center of Streets of Papunya, although I must say up front that that is a most personal judgment, reflective of my own history far more than Johnson’s. The first Papunya painting that I owned was a brilliant Water Dreaming by Long Jack Phillipus. The most startling early Papunya board I’ve ever fallen in love with is a Crow and Yam Dreaming by Limpi (at right), an artist I had never heard of until I saw the work reproduced in an auction catalog. For some reason I could never recapture, I was fascinated by the work of Two Bob Tjungurrayi; now having read Johnson’s book I understand that the brilliance of Turkey Tolson’s Straightening Spears paintings owes a great deal to stylistic innovations that Limpi and Two Bob undertook in the late 80s, before Turkey and his fellow innovator, Mick Namarari, themselves left the streets of Papunya behind. Reading about the heyday of Warumpi Arts, then located on Gregory Terrace around the corner from the old Papunya Tula shop, made me remember how thrilling it was in those days to be discovering the genius of the art of the central desert.