On my last trip to Europe, years ago, I got to check out the Pintupi show at Hamilton Gallery in London, attend the opening ceremonies at the Musée du quai Branly, view Gabrielle Pizzi’s astounding collection, and meet George Petitjean, curator of the AAMU Museum for Contemporary Aboriginal Art in Utrecht, the Netherlands. On my next trip to Europe, I’m going to go one better and make it to Utrecht to see the Museum itself. I just wish that I were able to do that before January 2014 when the current exhibition, BOMB, closes. Lucky for me that AAMU has published an excellent catalog documenting the installation.

On my last trip to Europe, years ago, I got to check out the Pintupi show at Hamilton Gallery in London, attend the opening ceremonies at the Musée du quai Branly, view Gabrielle Pizzi’s astounding collection, and meet George Petitjean, curator of the AAMU Museum for Contemporary Aboriginal Art in Utrecht, the Netherlands. On my next trip to Europe, I’m going to go one better and make it to Utrecht to see the Museum itself. I just wish that I were able to do that before January 2014 when the current exhibition, BOMB, closes. Lucky for me that AAMU has published an excellent catalog documenting the installation.

Although the core collections of AAMU are heavily weighted towards work from the deserts, Kimberley and Arnhem Land, the museum’s vigorous exhibition program has frequently stretched those boundaries, including, for example, a venue-wide installation by Brook Andrew, Theme Park, in 2008. They have also mounted several shows that pair Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal art. In 2010 Euro-Australian dialogues were investigated in Breaking with Tradition: CoBrA and Aboriginal art. An antipodean dialogue between Rusty Peters and New Zealand’s Peter Adsett, Two Laws … One Big Spirit (2007), featured fourteen paintings, painted by the two artists alternately responding each to the one by the other.

This year, it’s BOMB, in which Indigenous Australian Blak Douglas (the artist formerly known as Adam Hill) collaborates with Sydney’s Adam Geczy, a performance and installation artist who has exhibited extensively in Europe over the past decade. For context, 2013 is the tercentenary of the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the Wars of Spanish Succession, stripped France of much of its territorial possessions, and set the stage for England’s age of empire. In 1713, in the Netherlands, events were set in motion that would see the dimly discovered land of New Holland become the British colonial outpost of New South Wales.

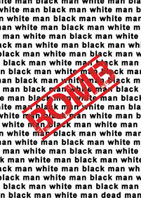

The collision of two cultures that resulted after 1788 is central to the imaginings of the two artists in this show. Let’s start with the cover of the catalogue itself, which reproduces a detail from the silk screen print Black Man White Man produced jointly by them. The print consists of its titular words reproduced over and over again. The type is offset just enough on each line so that one word can be read repeatedly in a strong diagonal from upper left to lower right. Your eye catches on “man” streaming down the page, or “black.” The words run together after a while, and that is no doubt intentional on the artists’ part. But on the catalog’s cover, the word BOMB has been superimposed in red, rubber-stamped like an official warning declaration. Contents under pressure? Imminent explosion possible?

But the real bomb of the show is a metaphorical one: a “bombed-out” BMW, retrieved from the desert junkyards and painted up. This is a vehicle laden with history, as only appropriate to the symbol of an exhibition that is part of a major historical celebration. In the 1970s and 1980s, BMW sought to boost its cultural cachet by commissioning artists to custom-paint a series of their vehicles as “Art Cars.” Participating artists have run the gamut from the sublime (Frank Stella) to the ridiculous (Jeff Koons). They were as celebrated as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, and as relatively unknown (at least in New York City, where the cars were displayed in a 57th St showroom) as Michael Nelson Jagamara. Jagamara joined the line-up of commissioned artists in 1989, no doubt in response to the Australian Bicentenary. (Interestingly, the other 1989 BMW commission went to Ken Done.) Jagamara’s BMW, like his design for the mosaic at the new Parliament Building, was an early example of a fusion of black art and white context; at the time it seemed like a promising sign that art would lead the way to reconciliation and recognition in the country’s third century.

As you can see, the “Bomb” in Utrecht, while obviously invoking Jagamara’s Art Car, fairly well explodes the myth of reconciliation with its superimposition of the Union Jack, and its “appropriation” of dot-styling, to the refuse of European marketing. The abandoned, bombed out car is the symbol par excellence of the lopsided exchange of value in the Aboriginal art market, the trade of paintings to be sold in a white cube for a vehicle that will most likely run for a few months before breaking down to rust abandoned on the outskirts of an outstation.

And yet the loving rehabilitation of the vehicle for this exhibition also speaks to the resilience of nomadic culture. The outstations would likely not have been established nor survived without the introduction of the vehicles that permitted Aboriginal people to return to their homelands and visit their country for purposes of cultural maintenance. The junkyards of dilapidated cars are the source of spare parts that keep other vehicles running, and the “art car” has a long tradition of its own in Indigenous art, from the painted car doors from Utopia through the fourth episode of Bush Mechanics.

BOMB is replete with multimedia works that attest to the intercultural conflicts and creativity that suffuse the modern Australian state and offer a critique of nationalism (once again the resonance of the Treaty of Utrecht comes to the fore) and the oppression that results from it. In the photograph above, an installation (on the wall, looking like a map of Australia) called Barbie Koori grafts images of Aboriginal women into photographs of beauty contests. For the opening of the exhibition, a performance piece of the same name had four white women in platinum blond wigs decked out as beauty-pageant contestants passing out leaflets in the street in front of AAMU: the leaflets provided statistical documentation of the violence, early mortality, and lack of economic opportunity that characterize the lives of Aboriginal women.

Another video installation flashes scenes of the ugly side of Australian identity–the racist nationalism that has infected places like Cronulla–to the soundtrack of a brutally revised version of “Advance Australia Fair” that asks “Do Australians really care?” In other videos, men project their anger at the camera smile and spit at the camera; an Australian flag tatoo is scraped off a man’s arm, leaving the skin irritated and red.

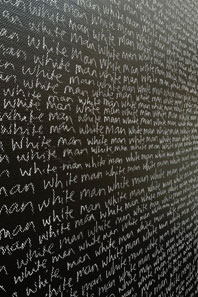

Wall paintings include a massive, meters-high wall covered with blackboard paint on which Adam Geczy has chalked the words “white man” over and over again like a schoolboy’s punishment until, at the very bottom, the words “dead man” appear, just once. A color-negative, reversed image of the Australian flag by Blak Douglas is further “desecrated” by an image of flames licking at one corner, while the stars of the Southern Cross, in the same reversed color scheme, are splayed across another wall as the stenciled graffiti emblem of a Boganvilliager. An array called Silver Bullet displays them nestled on velvet in wooden cases that look uncomfortably like simple pine coffins in miniature. The show is relentless, even in the catalog’s presentation.

In the video produced by the AAMU, “The Making of BOMB,” the artists describe the show as both a comedy dressed up as a tragedy and a tragedy dressed up as a comedy. The catalog offers more of the same, including a caustic essay by the two artists, “Aboriginal Art Diagnostic.” Dedicated to “Gustave Flaubert and the blackfella on the two dollar coin,” it concludes with a parody or an hommage to Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas. Douglas and Geczy’s version offers definitions and usage examples of terms like “authentic,” “gubbahriginal,” “leech,” “neologism,” (“a newly coined word or expression: Aboriginal art“), and “progressive” that are designed to skewer the art industry in ways that Richard Bell never dreamed of when he promulgated his theorem.

There is an excellent introduction to the exhibition by Georges Petitjean, and I’m indebted to Alisa Duff’s essay for the discussion of art cars above. The catalog concludes with a superb contribution from Ian McLean, “The Secret History of Performance Art.” Perhaps because I’ve been embroiled of late in so many discussions about Aboriginal art as contemporary art, and the possible relationships between the two classifications, I’ve been sensitized to the ways in which “art world” thinking characterizes and categorizes the work of Indigenous Australian artists. McLean’s essay focuses instead on the reception of Indigenous art; he neatly sidesteps the questions of authenticity, spirituality, and caste that Blak Douglas and Geczy satirize in their “Aboriginal Art Diagnostic.” Instead, by taking as his starting point Michael Fried’s critique of minimalism, which Fried saw as betraying the fundamental truths of modernism by being “ideological, anthropomorphic, and theatrical,” McLean is able to make a convincing case why Aboriginal art, especially as embodied in the Aboriginal Memorial, and by extension in BOMB, is decidedly not modernist art. (I should note that he does not position Aboriginal art as minimalist either, despite the fact that McLean feels that it partakes the of Fried’s defining qualities.)

Hill and Geczy create a carefully engineered space of conversation that not only puts in play a series of juxtaposed images/voices, contradictions and deconstructions designed to engage the viewer in dialogue, but also organises the space of the gallery in ways that re-embody the disembodied private space of disinterested aesthetic contemplation. … BOMB points to an outlaw history that the art museum proscribes: namely that Aboriginal art has always been relational not modernist (p. 93).

This assessment bears out Petitjean’s emphasis on the performative nature of the exhibition when he notes that “While the exhibition was being set up, a deliberate choice was made to keep the museum accessible to the public” (p.5). The video of “The Making of BOMB” demonstrates many of the ways in which this choice played out, in addition to offering smart, intriguing commentary by the artists. Watch it. It’s da bomb.

Of course, the place we really need this BOMB to explode is back here in Australia!

And as you say, Will, the ‘art car’ idea resonates way beyond the BMW story. I was so angry when Nicolas Rothwell recently dismissed the 2005 NATSIAA winning Tjanpi Toyota, made by women artists from Blackstone, as “kitschy”. What arrogant ignorance. Aside from their audacious conceptual innovation (from baskets to full sized truck in 10 years) and command of medium (it’s grass, it must be remembered!), the Toyota represents free access to Country and is the symbol par excellence of the exchange between Aboriginal artists and the outside world, both the good and the bad.

When Jimmy Donegan won the 2010 NATSIAA he said he would use his prize money to buy a “Toyota with lights”. When Mr Giles looked at his work as it had been recreated on the enormous facade of the Australian Film Television and Radio School in Sydney, his response was “that one’s worth two Toyotas”.

The new sign announcing the Amata Community in South Australia is a beautifully painted car bonnet (hood). The desert ‘tradition’ of painting car panels is alive and well.

Great article and review, thanks a lot Will!

Greetings from the AAMU team

Thanks Will. Much appreciated.

Adam Geczy

It’s a great show, Adam, thought-provoking an visually exciting. Thanks for stopping in.

Will

Hi Will, I just came back from Australia when you posted on your blog this excellent article on BOMB. Coincidentally, the day the article was posted was two days before the opening of “Australia” at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. It would be interesting to view these two exhibitions together. Each exhibition has ‘Australia’ as its theme and approaches this theme through art. Yet, the perspectives couldn’t differ more.

Georges

Indeed! I’m eagerly awaiting arrival of the catalog from the Royal Academy to see what all the fuss is about.

I recall having this same conversation with Adam Geczy about 25 years ago.

Pingback: Aboriginal Art Museum Utrecht | Aboriginal Art & Culture: an American eye

Pingback: Aboriginal Art Museum Utrecht | A Lifetime Is Required