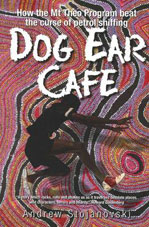

It’s rare that any publication about Indigenous matters generates as much buzz as Andrew Stojanovski’s Dog Ear Cafe: how the Mt Theo Program beat the curse of petrol sniffing (Hybrid Publishers, 2010) has in the scant weeks since its publication. Maybe it’s a commonplace for others these days, but this is the first book I’ve spent time with on Facebook. (Lots of great pictures, links to other reviews, and news stories to be found there.) It’s even rarer for all this media hype to be entirely justified.

It’s rare that any publication about Indigenous matters generates as much buzz as Andrew Stojanovski’s Dog Ear Cafe: how the Mt Theo Program beat the curse of petrol sniffing (Hybrid Publishers, 2010) has in the scant weeks since its publication. Maybe it’s a commonplace for others these days, but this is the first book I’ve spent time with on Facebook. (Lots of great pictures, links to other reviews, and news stories to be found there.) It’s even rarer for all this media hype to be entirely justified.

Like Rod Moss’s The Hard Light of Day, this is a story of Central Australia set mostly in the last decade of the twentieth century that nonetheless has startling relevance to the news of the moment. Stojanovski went to Yuendumu to serve as a school liaison officer after studying for a degree in anthropology. At first he tried to help the kids in town by running a variety of activities, including the local disco, that offered them the opportunity to socialize and dispelled the threat of boredom that often got them in trouble with the law. But he soon learned that crimes and misdemeanors were nowhere near as threatening to the community’s well-being as petrol-sniffing was. The violence that sniffing brought to Yuendumu was the external mirror of the violence that was being done to the brains and bodies of the teenagers who found addictive relief from their ennui in its fumes. And Stojanovski became one of the prime movers in the quest to eradicate the problem.

As he tells it, the real heroes of the story are a pair of elders, Peggy Nampijinpa Brown and Johnny Hooker Creek (Johnny Japangardi Miller), who took it upon themselves to take the incredible risk of bringing children who had been discovered sniffing to the Mt Theo Outstation on Peggy’s country about ninety kilometers northwest of Yuendumu. It might seem like such a simple plan to an outsider: remove the kids from the locus of temptation and keep their young bodies active and engaged with bush life.

But as Stojanovski’s narrative makes clear, it was anything but an easy plan to put into practice. The kids themselves didn’t want to be taken out bush away from their friends and their families. Nor did the families always desire to enforce such discipline on their unwilling and loudly protesting kids. Feeding such a mob wasn’t a simple proposition once they got them out there: Peggy and Hooker Creek might be skilled in bushtrade, but the kids themselves certainly weren’t, so food needed to be purchased, or begged, and carried out to the camp. Vehicles to transport supplies as well as people often had to be borrowed from other organizations in Yuendumu and jealousies over the use of these precious resources often ran high. (Not to mention that a vehicle arrived at Mt Theo carrying its own supply of the problem: enough petrol to make the return trip to Yuendumu.)

But perhaps the greatest act of courage lay in simply taking responsibility for an unruly and reckless mob of teenagers. The distance to be traveled back to town didn’t always stop the youngsters from trying to run away and risk being lost or hurt out in the desert. And if any one of the kids were injured, the full responsibility, including the very real possibility of payback, would have fallen on the organizers. One of the more harrowing moments in the story occurs when, early on, Stojanovski takes a high-spirited bunch out for a swim at a distant waterhole and has an accident: he’s blamed for risking harm to the child and for inappropriate use of a government vehicle and suffers a period of intense fear and recrimination on both counts, despite his best intentions.

Indeed, it often seems that there are no rewards to be had for these extended, herculean labors. Stojanovski’s family suffers for his idealism, government officials squabble over pittances, internal Aboriginal politics threaten to collapse the fragile structure of relief over and over again. Recidivism is always only one night in Yuendumu away from undoing weeks and months of hard work. At times it seems that the only thing that keeps Peggy, Johnny, and Andrew going is their own determination to keep going: they simply will not quit until they’ve eradicated sniffing. The goal becomes its own reward. Even though the trio were ultimately awarded the Order of Australia for their services and the program became recognized as a model for community intervention across the country, the only thing that truly matters to them throughout is keeping the kids clean and healthy.

Eventually their efforts do become self-reinforcing as some of the kids take on the fight themselves. Jaru Pirrjjirdi (Strong Voices) grew up to be a mentoring program in which former sniffers themselves organized a variety of cultural activities, including the new arts of film-making and music production alongside painting and hunting and sports, that offered diversion to new sniffers while providing meaning and direction to those who had reformed themselves.

In a nutshell, this is the story of Dog Ear Cafe; but the story is only half the story, so to speak. A great deal of the appeal of this memoir lies in Stojanovski’s voice. Although he and his allies encounter much opposition and red tape and must battle community politics, Stojanovski names names at each step of the battle and never sounds petulant. In this respect, his account of travails in Yuendumu stands in stark opposition to the tone of Chris Raynal’s Yuendumu: betrayal of black rights (Blue Water Publishing, 1990), which chronicles affairs in the town just a few years before Stojanovski’s arrival there. Both men share a passion for their cause, and the welfare of the Indigenous population; both are equally convinced of the righteousness and justice of what they are fighting for. But Stojanovski’s voice is one of dogged determination: there is nothing that will prevent him from stamping out the scourge of sniffing and every setback only redoubles his conviction and his ingenuity.

Like many memoirists, Stojanovski gives life to his story by reconstructing bits of dialogue that must have occurred a decade or more before he committed them to paper. But since his narrative style overall is conversational, these minor inventions slip noiselessly into the story and do much to give the reader the feel of being there, fireside, in the troopie, or stalking through the bush. He has an apt way with metaphor when he needs it as well. In conversations with Hooker Creek, he remembers talking about the two of them being tightrope walkers, each starting out from their respective sides of the cultural chasm in an attempt to meet the other halfway across. Their compatriots, white and black, stand behind them on the rim of the abyss and are sometimes given to shaking the tightrope in an attempt to make the two men falter and fall.

The struggle takes a toll on family relations as well. Stojanovski’s wife goes back to Canberra, and Stojanovski himself has to retreat, assess, and battle with his conscience about where he rightfully belongs. On the Warlpiri side, Peggy Nampijinpa Brown has to make an equally if not more difficult decision when her husband, Old Japangardi, dies. By law, she ought to abandon the Mt Theo Outstation for the proscribed period of sorry business, but she decides, with community support, that to do so would endanger the welfare of too many youngsters. She shoulders on despite the taboos.

Dog Ear Cafe is a wonderful (literally) chronicle of a crusade. After over a decade’s work to establish the program at Mt Theo, Stojanovski himself moved on, turning his time over to raising his daughters in rural NSW–and writing this book. An afterward by Brett Badger brings the story up to date, and a slew of useful appendices includes a list the people who appear in the story and the relations among the them, an elementary, brief Warlpiri glossary, a list of place names, and a bibliography of further reading.

Another appendix provides a short description of “the mechanics of the Mt Theo petrol sniffing prevention program.” If you wants more information on the current state of operations, check out the Mt Theo Program website. There’s news about the Mt Theo mechanics program (more bush mechanics!) and an update on the Yuendumu swimming pool, plus posters, biographies, and a blogroll of Yuendumu-related sites ranging from PAW Media (formerly Warlpiri Media Assocation) and Warlukurlangu Artists to the Yuendumu Magpies.

The Sydney Morning Herald called Dog Ear Cafe “a story of hope from Aboriginal Australia.” The excerpt they published shows how harrowing the battle could be at times. That much of this battle occurred under the Coalition and CLP governments makes it all the more amazing and inspiring: it shows what collective grit can accomplish in the face of indifference. It’s not too late, never too late, to be inspired.

Quite simply: inspiring modern day heroes.

Pingback: Dog Ear Cafe Launch | Me fail? I fly!

Pingback: Emily Tempest Returns | Aboriginal Art & Culture: an American eye